The Scoop (TL;DR)

Context engineering is the next evolution beyond prompt engineering, focusing on curating and managing all relevant information provided to large language models (LLMs) to maximize performance, reliability, and scalability for production-grade AI systems. Instead of relying on single, static prompts, context engineering assembles dynamic, multi-component payloads (including instructions, external knowledge, memory, state, and tools) to build robust, context-aware workflows.

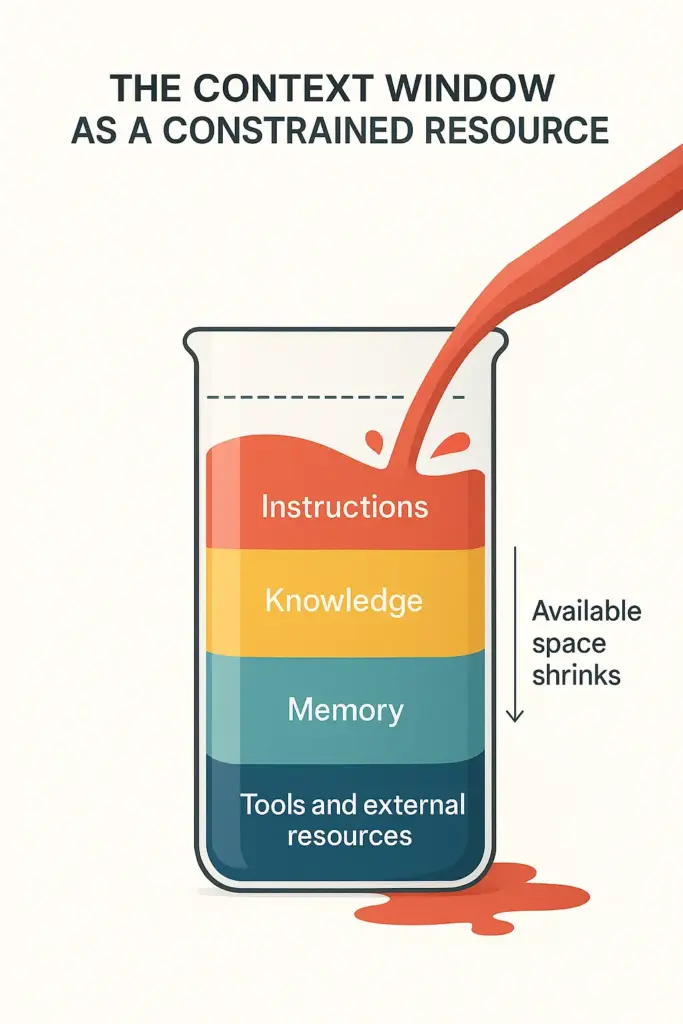

Key concepts include managing the LLM’s finite context window through retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), memory systems, structured tool integrations, and optimized input/output formats. The framework emphasizes mitigation strategies for common context failures (e.g., context poisoning, distraction, confusion, clash), advocating for practices like validation, summarization, pruning, and tool loadout management.

Enterprise-grade AI requires context engineering to overcome challenges such as scalability, reliability, economic efficiency, and compliance, shifting focus from clever prompts to rigorous information architecture, unlocking true autonomous agent capabilities and consistent, trustworthy AI outputs.

The Paradigm Shift from Prompt to Context

As artificial intelligence applications have evolved from simple chatbots to complex, multi-agent workflows, the limitations of crafting single, static prompts have become a significant architectural bottleneck. The core challenge is the management of a Large Language Model’s (LLM) finite attention budget, its limited “working memory.” The initial focus on “prompt engineering” proved inadequate for building robust, stateful systems, necessitating a more systematic approach: the shift from crafting prompts to engineering context. This evolution represents a fundamental maturation in AI system design, moving from tactical tweaks to a coherent architectural philosophy centered on optimizing this constrained resource.

The Limitations of Static Prompting

Relying solely on prompt engineering for complex AI applications presents several core challenges. This approach often treats the LLM as a stateless function, where each interaction starts fresh, a method akin to “blind prompting”, asking a question without providing the necessary background information. However, advanced applications require state management, dynamic data integration, and the orchestration of external tools to perform reliably.

The limitations of static prompting can be understood through the “movie production” analogy. If prompt engineering is writing a single, clever line of dialogue for an actor, context engineering is the entire process of building the set, designing the lighting, providing a detailed backstory, and directing the scene. Without the engineered context of the set and scene, the line of dialogue (the prompt) lacks meaning and impact. Similarly, an LLM without engineered context is merely an actor on a blank stage, forced to improvise with no script, background, or direction.

The Rise of Context Engineering

Context engineering is the natural and necessary evolution for building industrial-strength AI. It is the discipline of designing and optimizing the complete information payload provided to an LLM at inference time, encompassing not just instructions but also relevant knowledge, memory, and tools.

This paradigm shift has been recognized by influential figures across the AI landscape. Andrej Karpathy defines it as the art and science of curating what will go into the limited context window from a constantly evolving universe of possible information (Post on X). Shopify CEO Tobi Lutke frames it as “the art of providing all the context for the task to be plausibly solvable by the LLM.” (Post on X) These perspectives underscore a move away from simple instructions toward a holistic, architectural approach to information management.

From Tactical Prompts to Strategic Systems

The shift to context engineering is strategic, not merely semantic. It marks the transition from “strings to systems,” where principles of systems architecture, memory management, and information retrieval are applied to AI development. Instead of focusing on tactical “prompting tricks,” developers are now architecting the entire information environment in which an AI operates. To design, optimize, and evaluate these context-aware systems systematically, we require a more formal and rigorous definition of this new discipline.

A Framework for Context Engineering

Moving beyond anecdotal techniques requires a clear conceptual framework. Defining context engineering systematically provides the foundation to design, optimize, and evaluate context-aware systems in a measurable way. This clarity is essential for managing the LLM’s finite attention budget and building applications that meet the reliability demands of enterprise environments.

Differentiating from Prompt Engineering

Context engineering is not just a new name for prompt engineering; it is a fundamentally different discipline in scope, complexity, and objective. The following table provides a clear, side-by-side comparison.

| Dimension | Prompt Engineering | Context Engineering |

| Scope | Single, static string of instructions. | Dynamic, multi-component information assembly. |

| Optmization Target | Maximizing performance for a single query. | Maximizing expected performance across a system of components. |

| Complexity | Simple, one-time context assembly. | Multi-component optimization involving retrieval, filtering, and orchestration. |

| Stage Management | Primarily stateless. | Stateful, incorporating memory from conversation history. |

| Scalability | Performance degrades linearly with prompt length. | Achieves sublinear scaling through compression, filtering, and strategic information placement. |

| Information Sources | Typically limited to the prompt itself. | Integrates multiple sources: knowledge bases, tools, memory systems, real-time data. |

The Core Components

In context engineering, the information provided to an LLM is not a simple string but a structured assembly of multiple, carefully curated components:

- Instructions: System prompts, rules, and behavioral guidelines that define how the model should operate

- Knowledge: Relevant information retrieved from external sources through techniques like Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)

- Tools: Definitions of available functions or APIs the agent can call to interact with external systems

- Memory: Both short-term conversation history and long-term learned facts persisted across sessions

- State: The current state of the user, the task, or the external world

- Query: The user’s immediate request or question

The Optimization Challenge

Context engineering is fundamentally about finding the optimal way to assemble these components within critical constraints:

Primary Constraints:

- Token Limits: The complete context must fit within the model’s maximum token capacity

- Relevance: Retrieved knowledge must be pertinent to the current query

- Coherence: Memory selection must maintain conversational flow and logical consistency

- Accuracy: State information must reflect current, factual conditions

Optimization Goals:

- Maximize the quality and relevance of information provided

- Minimize noise and irrelevant details that could distract the model

- Balance completeness with conciseness

- Maintain consistency across multiple interactions

- Ensure the context enables the model to generate accurate, useful outputs

The challenge is that these goals often conflict. More information isn’t always better; adding irrelevant context can actually degrade performance, a phenomenon we’ll explore in Mitigating Context Failures. Context engineers must make strategic decisions about what to include, what to exclude, how to structure information, and when to retrieve additional details.

Why This Matters?

This shift from simple prompting to systematic context engineering represents a maturation of AI system design. Rather than treating the LLM as a magic black box that responds to clever phrasing, context engineering recognizes that:

- Information architecture determines outcomes: The way information is structured and presented matters as much as what information is provided

- Context is dynamic, not static: Effective systems adjust what context they provide based on the task, user, and conversation state

- The context window is a precious resource: Like any constrained resource in computing, it must be managed carefully and strategically

- Multiple components must work together: Tools, memory, retrieval, and instructions must be orchestrated as an integrated system

With this conceptual framework established, we can now examine the practical, high-signal components that engineers use to populate the context window effectively.

The Anatomy of Engineered Context: Core Components

Context engineering comes down to three capabilities: what your AI knows, what it remembers, and what it can do. RAG handles knowledge retrieval. Memory systems manage conversation history and state. Tools provide the ability to interact with external systems. Get these right, and everything else follows.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) is a cornerstone technique for injecting external, up-to-date knowledge into the LLM’s context window. Its primary function is to combat hallucinations and overcome the static knowledge limitations of pre-trained models. By searching external knowledge bases for relevant information and including it in the context alongside the user’s query, RAG grounds the model in factual, timely data, dramatically improving the accuracy of its responses.

Memory Systems

For an AI to engage in coherent, long-running conversations, it needs memory. Context engineering involves designing and implementing various memory systems to manage state and persist information.

• Short-Term Memory: This corresponds to the information held within the LLM’s immediate context window for a single session, enabling it to track the conversational flow, recall recent user statements, and maintain coherence in multi-turn dialogues.

• Long-Term Memory: This involves persisting information across different sessions. Common implementations include retrieving relevant knowledge from a vector store (e.g., past user preferences) or caching the results of previous queries to improve efficiency and reduce costs.

• Structured Note-Taking: In this advanced strategy, an agent persists notes to an external memory, such as a NOTES.md file. This is especially useful for complex, long-horizon tasks where the agent needs to track progress, key decisions, or intermediate results, particularly across context window resets.

Tool Use and Function Calling

Tools and function calling provide AI agents with “proxy embodiment”, the ability to act upon and retrieve information from an external environment. This transforms the AI from a passive text generator into an active agent that can perform tasks. For example, providing an agent with a tool to get the current date and time eliminates guesswork and dramatically improves the accuracy of time-sensitive queries, such as “find me news from last week.”

Structured Inputs and Outputs

Architecting the structure of both the input and expected output is a critical discipline for ensuring consistent, machine-parsable results. Structuring the input, for instance by using delimiters like <user_query>, helps the model clearly distinguish user input from system instructions. Equally important is structuring the expected output. In the “Search Planner” agent example, the system prompt provides a detailed schema and a JSON example of the desired format, ensuring the agent produces a consistent result that can be reliably passed to downstream components.

In advanced systems, these components are deeply intertwined. An agent might use a tool to query an external API, store the result in short-term memory for immediate use, and leverage RAG to retrieve a historical document that provides context for interpreting that API result. While these components are the fundamental building blocks, their true power is only realized when they are orchestrated within a coherent architecture designed to manage the context window across complex, long-running tasks.

Implementation Strategies and Architectures

Individual components matter, but architecture matters more. Below, I’ll walk through a concrete example of how to structure a single agent’s context, then cover the architectural patterns you’ll need when tasks exceed your model’s context window, which happens more often than you’d think.

Practical Example: The “Search Planner” Agent

The system prompt for a “Search Planner” agent provides a concrete example of context engineering in action, combining multiple components to guide the agent toward a specific, structured output.

1. High-Level Instructions: The context begins with a clear role and task definition.

2. Dynamic Context: The prompt dynamically injects real-time information using a placeholder (e.g., {{ $now.toISO() }}) that is replaced with the current date and time at inference. This grounds the agent in the present and is critical for time-sensitive queries.

3. Structured Output Definition: The context provides explicit instructions and examples for the desired output format, ensuring the results are consistent and machine-parsable.

4. Inference and Tool Integration: The context instructs the agent to infer additional information based on the provided data, demonstrating how engineered context can trigger further processing steps.

Architectures for Long-Horizon Tasks

When a task’s complexity requires more tokens than the LLM’s context window can hold, specialized architectural patterns are needed. These techniques focus on managing, compressing, and selectively recalling information over extended interactions.

• Compaction This is the practice of summarizing a conversation’s history to create a compressed context for a new session. When a conversation approaches the context window limit, the model is tasked with distilling the most critical details while discarding redundant content. This allows the agent to maintain long-term coherence, though it introduces a trade-off: an overly aggressive summary risks discarding a subtle but critical detail that only becomes relevant later.

• Structured Note-Taking (Agentic Memory) This strategy involves having the agent persist key information, progress updates, and plans to an external file (e.g., a NOTES.md file). This external memory can be re-loaded into the context as needed, allowing the agent to track complex dependencies and maintain its strategic direction across context resets. It provides a persistent, low-overhead memory that would otherwise be lost.

• Sub-agent Architectures This approach involves delegating focused tasks to specialized sub-agents. A main “orchestrator” agent manages a high-level plan and assigns specific sub-problems to worker agents, which return a condensed summary of their findings. This allows the main agent to manage a complex project without being overwhelmed by low-level details, but it introduces the architectural cost of added orchestration complexity and potential communication overhead between agents.

The Role of Protocols: MCP

Standardized protocols are emerging to simplify the integration of external context sources. The Model Context Protocol (MCP) is a mechanism that allows tools to be plugged into an AI system as “context providers.” It defines a standard API so that any tool, from a database to a search engine, can be integrated with an AI agent, abstracting away the complexity of custom integrations. While these strategies are powerful, they are also susceptible to specific types of failures that must be actively mitigated.

Mitigating Context Failures: Common Pitfalls and Solutions

Robust system design must treat the context window as a constrained resource susceptible to predictable failure modes, such as context rot and attention degradation. A proactive architecture anticipates and mitigates these failure modes by design. Even with large context windows, models are vulnerable to issues that can degrade performance, and a resilient system must account for these possibilities.

The Challenge of Large Context Windows

Counter-intuitively, ever-larger context windows do not automatically solve context management challenges. Research has consistently identified the “lost in the middle” problem (1), where models pay disproportionate attention to information at the beginning and end of the context, frequently ignoring critical details buried in the middle. This is not a theoretical concern; one study from Databricks found that a model’s correctness can begin to drop significantly once the context exceeds just 32,000 tokens, long before the theoretical limit is reached, demonstrating that precision and relevance are far more critical than raw context size (2).

A Taxonomy of Context Failures

Several distinct types of context failures have been identified, each with its own cause and characteristics (3).

• Context Poisoning This occurs when a hallucination or factual error enters the system’s context and is then repeatedly referenced in subsequent turns. Once poisoned, the context can lead the agent to pursue nonsensical strategies or build upon a flawed premise, making recovery difficult.

• Context Distraction When the accumulated context history grows too large, the model may begin to focus excessively on past actions or information, causing it to repeat itself instead of developing new, relevant strategies. This is often observed when token counts exceed a model’s practical attention limit.

• Context Confusion This failure happens when irrelevant tools or extraneous information are included in the context. This can confuse the model, causing it to generate poor responses, call the wrong tools, or become sidetracked by information that is not pertinent to the current task.

• Context Clash This occurs when information is provided in stages. The model may make an early assumption based on incomplete data, and this incorrect assumption remains in the context, clashing with more complete information provided later, leading to contradictory reasoning.

Mitigation Patterns and Best Practices

For each type of context failure, specific engineering patterns have been developed to mitigate the risk. These strategies focus on actively curating, validating, and structuring the context to maintain its integrity.

| Failure Type | Recommended Mitigation Strategy |

| Context Poisoning | Context Validation and Quarantine: Isolate different types of context and validate new information before it is added to long-term memory. Start fresh threads to prevent bad information from spreading. |

| Context Distraction | Context Summarization (Compaction): Instead of letting context grow indefinitely, compress the accumulated history into shorter summaries that retain critical details while removing redundant information. |

| Context Confusion | Tool Loadout Management: Use RAG-based techniques to dynamically select only the most relevant tools for a given task. Storing tool descriptions in a vector database and retrieving them on-demand can significantly improve tool selection accuracy. |

| Context Clash | Context Pruning and Offloading: Actively prune outdated or conflicting information as new details arrive. Provide the model with a separate workspace or “scratchpad” to process information without cluttering the main context. |

Enterprise Implications and the Future of AI Development

Mastering context engineering is rapidly becoming a core enterprise capability. It is the key to moving artificial intelligence from experimental pilots to reliable, production-grade systems that generate measurable return on investment. As organizations scale their AI initiatives, the ability to architect and manage context will be a primary determinant of success.

Addressing the Core Bottleneck

Most failures in modern agentic systems are not caused by flaws in the core model’s reasoning but are instead “context failures.” Industry data suggests that over 40% of AI project failures stem from providing poor or irrelevant context. Context engineering directly addresses this bottleneck by instilling the discipline needed to ensure reliability, consistency, and auditability in AI-driven workflows.

The Demands of Production Systems

Enterprise environments have stringent requirements that go far beyond what simple prompting can satisfy. Context engineering provides the architectural foundation needed to meet these demands.

• Reliability and Consistency: Ensuring predictable outputs and graceful error handling through structured inputs and outputs.

• Scalability Beyond Simple Tasks: Managing stateful, long-running workflows in complex, data-rich environments via memory systems and advanced architectures.

• Economic and Operational Efficiency: Optimizing token usage, managing latency, and enabling the systematic maintenance of knowledge bases.

• Compliance and Governance: Providing transparency in how context influences decisions and enabling adherence to regulatory standards through auditable information pipelines.

The Future is Context-Aware

Context engineering represents a fundamental maturation of AI system design. It is the architectural discipline that will unlock the full potential of Large Language Models. By moving beyond prompt crafting to the systematic engineering of information, we enable the transition from simple text generators to autonomous agents and sophisticated AI copilots that can operate reliably and effectively in the complex, dynamic environments of the real world.

Final Words

Context engineering is the essential discipline for building production-grade artificial intelligence. It marks a critical evolution from the tactical craft of writing individual prompts to the strategic, systematic architecture of information. By assembling and managing a complete payload of instructions, knowledge, tools, and memory, this approach addresses the primary bottleneck preventing AI from achieving reliable, enterprise-scale deployment. As we move forward, it is clear that context is not just an add-on; it is the foundational element that will unlock truly intelligent, consistent, and trustworthy AI systems capable of tackling the world’s most complex challenges.

References

(1) Liu L, Bai P, Liu C, Tian W, Liang K. “Lost in the Middle: How Language Models Use Long Contexts.” Stanford University; 2023. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.00000

(2) Databricks. “Long Context RAG Performance of LLMs.” Databricks Blog, August 18, 2024. Available at: https://databricks.com/blog/long-context-rag-performance

(3) Drew Breunig. “How Long Contexts Fail.” June 22, 2025. Available at: https://www.dbreunig.com/2025/06/22/how-contexts-fail-and-how-to-fix-them.html

Further Reading

For readers interested in exploring context engineering further, we recommend these resources:

Prompt Engineering Guide. “Context Engineering Guide.” Available at: https://www.promptingguide.ai/guides/context-engineering-guide

Comprehensive practical guide with concrete examples of building multi-agent systems and detailed code walkthroughs.

DataCamp. “Context Engineering: A Guide With Examples.” Available at: https://www.datacamp.com/blog/context-engineering

Accessible introduction covering context failures, RAG systems, and practical implementation patterns.

Microsoft. “Context Engineering Guide.” Visual Studio Code Documentation. Available at: https://code.visualstudio.com/docs/copilot/guides/context-engineering-guide

Practical implementation guide for developers using GitHub Copilot and AI coding assistants.

arXiv. “Context Engineering for Multi-Agent LLM Code Assistants Using Elicit, NotebookLM, ChatGPT, and Claude Code.” arXiv:2508.08322v1; 2025. Available at: https://arxiv.org/html/2508.08322v1

Advanced exploration of multi-agent architectures for complex repository-level coding tasks.